The First Line of Flavor: Weeknight Thai Aromatic Stir-Fry

Fresh Aromatics, Thai Flavor, and Why Curry Was Never Just a Powder

“Curry powder” is a British invention. And also, not at all.

Long before curry became something measured by the teaspoon, it began with sound and smell. Fresh roots pulled from the ground. Grasses cut to their tender cores. Leaves torn just enough to wake them up. Flavor came from living plants and from knowing what they did to the body as much as how they tasted.

This is where Thai flavor actually starts. Not with heat, but with relationships between ginger, lemongrass, galangal, lime, and chilies where the aromatics hit the oil and everything starts to feel like magic.

In this post, we’ll talk history and digestion, yes. But we’ll also make a fast, deeply satisfying Thai-inspired stir-fry you can pull off on a tired Tuesday night, without special equipment or culinary gymnastics.

Hey food friends! 👋 I’m Kaitlynn a software engineer turned kitchen-experimenter, half of a food-loving couple 🍜 exploring DC (& beyond) who knows the best connections happen at a shared table 🍽️. Whether you're searching for the best hidden restaurants in Mexico City, trying to master your grandma's marinara 🍅, or just craving something real, I’m here with dishes (and discussions) that make life more interesting. Come hungry, leave inspired. ✨🍴

Welcome to the Golden Middle Kitchen, a series for anyone who might be thinking, “I want my nervous system to unclench, but I also want dinner to slap.”

Sparked by a deeply satisfying bowl of curry on a cold day, the series follows ingredients, techniques, and ideas that show up again and again across kitchens and cultures along the spice road. By deconstructing and occasionally reconstructing familiar dishes, these posts trace patterns that repeat across climates and centuries: soft power and hot spices, warming fats, grounding roots, and the gentle, steady work of steam and spice.

The series draws loosely from Thai food traditions, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, and everyday kitchen knowledge that have fed people well for up to 3,000 years. Many of these systems developed independently, in different parts of the world, yet arrived at strikingly similar conclusions. The best ideas tend to do that, and Western science seems to just be catching up.

This is more about balance, nourishment, and food that feels good to cook and eat than optimizing anything. I’m not a chef or a clinician, just a regular human learning through cooking and reading. If you’re curious too, historically and practically, come pull up a chair.

The First Line of Flavor

There’s a much bigger global history to curry, and we’ll keep pulling on that thread as this series unfolds. But for now, we’re zooming in on where curry actually begins in the pan: fresh aromatics.

They hit hot oil first. They perfume the kitchen. They set the tone for everything that follows. They are intended to have a functional effect on the body as well as flavor-building. Warm digestion. Cool excess heat. Move energy. Settle the stomach. Sharpen the senses. Cooking and medicine were overlapping skills.

If you’ve ever wondered why ginger seems to calm your stomach, why coconut-rich curries don’t feel as heavy as they should, or why a dish built from a handful of humble roots can feel both energizing and grounding, you’re already asking the right questions. We’re going to keep looking at what modern nutrition science is recognizing and traditional systems like Ayurveda have been saying about these ingredients for centuries, and how they work together in real food.

And yes, we’ll also talk about how to do this on a weeknight, without a mortar and pestle, while your brain is fried and everyone is hungry.

Aromatics Are Not Exactly Spices

Spices are often dried, ground, shelf-stable. Aromatics are fresh. Alive. They work largely due to beneficial volatile oils in the plant. They hit hot oil or hot water and send a signal to your nervous system before you’ve even tasted anything. They say,“Pay attention, something good is coming”.

In Southeast Asian cooking, and especially in traditional Thai curry, that first line of flavor is built from the fresh aromatics we’ll focus on in this post: ginger, galangal, lemongrass, makrut lime leaves and thai chilies. These aren’t added by the teaspoon. They’re crushed, sliced, torn, and bloomed in oil to release volatile oils that shape both flavor and digestion.

Refined over centuries by cooks in hot, humid climates who needed food to do more than taste good. Meals had to nourish, digest easily, and sometimes protect the body from inflammation, spoilage, microbes, or heat stress. Again, cooking and medicine were the same skill set, expressed through dinner.

Think of what follows as a miniseries. Same pan. Same moment in the oil. Very different personalities.

We start with ginger, because ginger is often the first one to arrive, historically and biologically. And, even today as its been for millenia, she’s kind of the mega-star of this crew, the ingredient that learned how to travel, translate, and make everything else get along.

Panang Aromatic Chronicles

A Family Drama in Three Acts

Thai curry pastes and stir-fries don’t start with heat.

They start with relationships.

Long before anyone called this food “Thai,” aromatics were already doing what they’ve always done best in Southeast Asia: feeding people and keeping them functional. Cooking and medicine weren’t separate disciplines. A meal was supposed to do something. Help digestion. Reduce inflammation. Balance the body. Keep microbes from setting up camp.

That’s why these plants show up together, again and again, especially in coconut-based curries like Panang and in Thai-inspired stir-fries built on aromatic pastes.

Act I: Ginger The Translator & Lemongrass The Homebody

Growing up together as perfect opposites.

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus and related species) grew up in the same humid belt of South and Southeast Asia. Same rains. Same soils. Same kitchens. Ginger and lemongrass were never strangers, but they didn’t take identical paths.

Both live at the intersection of traditional Southeast Asian cooking and herbal medicine. You find them in soups, curry pastes, broths, teas, and tonics because they share a job description: make rich food digestible and the body feel better afterward.

Scientifically, they complement each other almost suspiciously well.

Ginger contains gingerols and shogaols, compounds shown to stimulate digestion, increase gastric motility, improve circulation, and reduce nausea and inflammation. In Ayurvedic and traditional Asian medicine, ginger is considered warming and activating. It lights the stove. Gets things moving.

Lemongrass brings citral and other volatile oils with antimicrobial, antispasmodic, and calming effects. Its aroma is citrusy, green, and bright. In food science terms, it cuts fat and lifts aroma. In traditional medicine, it soothes the digestive tract and cools excess internal heat.

Near perfect balance. Ginger warms and mobilizes. Lemongrass refreshes and steadies. One pushes, the other smooths. This is why Thai curries can be rich with coconut milk yet still feel clean, vivid, and oddly energizing instead of heavy.

Before European spice routes flattened too much into powders, ginger and lemongrass were already traveling the Indian Ocean world through Austronesian and South Asian trade networks as fresh plants, preserved roots, and living medicine.

But while they grew up together, only one of them became a global celebrity.

Ginger is one of the most widely traveled food plants in human history. Indigenous to Maritime Southeast Asia and domesticated over 5,000 years ago, it moved early and often. By the time European empires arrived, ginger was already embedded in Chinese cooking, Indian Ayurveda, Middle Eastern spice blends, and eventually medieval European kitchens. Ginger learned how to speak a lot of culinary languages, showing up in any kind of dish from dessert to medicine.

In Ayurvedic terms, it’s considered agni-deepana — a kindler of digestive fire.

From a nutritionist’s point of view, this is no accident. Ginger is one of the most broadly tolerated medicinal foods on the planet. It doesn’t just soothe nausea; it helps the body process what comes next. Modern research backs this up: compounds like gingerol and shogaol increase gastric motility, improve circulation, and reduce inflammation without suppressing digestion.

This is why ginger shows up at the beginning of meals, in broths, teas, and pastes. It prepares the system. It translates rich food into something the body knows what to do with.

In cooking, ginger behaves the same way. It doesn’t dominate a dish. It settles it. It rounds sharp edges, gives sweetness somewhere to land, and makes bolder flavors feel friendlier.

If ginger has a personality, it’s hospitable. It makes introductions.

Lemongrass never chased that life.

Bulky, fibrous, and dependent on fresh volatile oils, lemongrass doesn’t dry or ship well. Its magic fades fast once cut. For most of history, that meant it stayed close to home.

Instead of spreading outward, lemongrass sank deeper. It became essential to the people who really knew it - Vietnamese pho masters, Thai curry makers, Malaysian rendang cooks.

Where ginger is warm and grounding, lemongrass is bright and clarifying. Its citrusy aroma lifts richness and cuts through fat. In traditional medicine systems, it was valued for calming digestion, easing cramps, and cooling excess internal heat. In the kitchen, it makes rich food feel lighter and broth feel alive.

One traveled. One stayed.

Together, they created harmony.

But this family had elders. Ancient ones. And they set the tone.

Act II: Galangal & Makrut Lime

The Ancestors Who Define the House

Galangal (Alpinia galanga), often called Siamese ginger, is not ginger’s twin. It’s from the Alpinia family, tougher, paler, sharper.

If ginger is the friendly uncle, galangal is the medicine man in the corner who sees straight through you.

It tastes piney and medicinal, and piercing, with a citrus snap that cuts through richness cleanly. Traditional healers used it for digestion, respiratory health, and what they called “clearing wind from the body.” It doesn’t soothe. It clarifies. Focuses.

Food historians trace galangal in Southeast Asian cooking back well over a thousand years. It was here before Thailand was Thailand. This is one of the flavors that makes Thai food taste unmistakably Thai. Not spicy. Not sweet. Exact.

Its longtime partner is makrut lime. Not the fruit. The leaves. Those glossy, double-lobed figure-8 leaves that smell like citrus wandered into a flower garden and never came back. While regular limes were being practical (juice! cocktails! ceviche!), makrut lime was busy being unforgettable.

Much to the chagrin of many experienced chefs and home-cooks, you can’t substitute it. There’s no equivalent. It’s that specific, that singular. Makrut lime is so Southeast Asian it barely exists in Western food outside this context.

Traditional medicine paired them for respiratory health and digestion. Galangal cuts. Makrut lime opens. Both are considered “cooling” in Thai traditional medicine, balancing the body’s wind element. This pairing is ancient. Foundational. Possibly over a thousand years old.

Science backs the old instincts. Compounds like galangin in galangal and citronellol in makrut lime leaves show antimicrobial activity, helping explain why these two were paired long before anyone owned a microscope.

These two are the OGs.

The baseline.

The reason Thai food tastes like Thai food and not like anything else.

If ginger makes introductions, galangal and makrut lime run the room.

That’s how things worked for centuries. Then came the plot twist.

Act III: Thai Chilies

The Immigrant That Rewrote the Rules

Thai chilies (Capsicum annuum and Capsicum frutescens) aren’t Thai at all.

They’re Indigenous to the Americas, domesticated in Mexico, Central America, and South America thousands of years ago. They arrived in Southeast Asia in the 1500s through Portuguese traders as part of the Columbian Exchange, that massive, world-altering swap of crops, animals, diseases, and ideas.

Before chilies, Thai food still had heat. Just not that heat.

It came from black pepper, long pepper, ginger, and galangal. The food was complex, aromatic, and restrained.

Then chilies arrived.

They were hotter than anything the region had tasted. They grew easily in Thailand’s climate. Within a century, they became inseparable from Thai cooking. By the 1800s, food historians note that Thai cuisine without chilies was almost unthinkable, as if they’d always been there, waiting for this exact soil and this exact flavor system.

Traditional healers paired chilies with galangal almost immediately. Capsaicin from chilies and galangin from galangal work on complementary anti-inflammatory pathways. Heat that opens circulation. Compounds that calm inflammation. Fire that heals.

It’s a story we’re familiar with - the immigrant became more native than the natives. The outsider became essential. Take note, this is how the world works. Don’t believe me? Ask an Italian about tomatoes, or a Frenchmen where Vanilla came from, or the Swiss about chocolate (hint: they all came from Mexico ;)

Chilies aren’t quite exactly aromatics.

They don’t build the foundation. They arrive later. They amplify. They provoke.

The Takeaway

This Is the Story You’re Cooking

When you make a Thai-inspired stir-fry or curry paste, you’re staging a reunion.

Ginger and lemongrass, the balancing siblings.

Galangal and makrut lime, the ancient anchors.

Chilies, the revolutionary immigrant who changed everything.

You pound them together to re-introduce them. You fry them in hot oil to wake them up, releasing those gorgeous volatile essential oils they just can’t hold back.

They say hello, we’re here, and we’re so different and we’re a little all over the place, but when we work together just being ourselves, it’s pretty amazing.

When you taste it, you’re tasting centuries and millenia of cultural wisdom colliding into something that supports your body to keep doing what it needs to do.

That’s not just dinner.

That’s embodied cultural knowledge in the deepest possible way.

Where to find

Lemongrass, ginger, and thai chilies seem to be pretty available in big chain grocery stores.

If you’re like me, you didn’t really have galangal or makrut lime leaves on your radar before this, and they are more likely to be found in specialty Asian or international grocery stores, possibly in the frozen section. In my area I found some at H-mart.

🍋 Weeknight Thai Aromatic Stir-Fry

Curry thinking (fresh aromatics, flavor depth, digestion-aware flavors) applied to stir-fry technique (high heat, fast cooking, and that satisfying crunch) at weeknight speed.

Serves 2–3 | ~20 minutes

🧠 The Approach

Protein browns first.

Veg stays crisp

Aromatics bloom briefly

Everything reunites fast at the end

Cook in parts. Finish together. No burning. No mush.

🌿 Aromatic Paste (5 min)

Rough paste, not baby food.

1-inch ginger, sliced

1-inch galangal or extra ginger, sliced

1 stalk lemongrass (white part), sliced

3–4 makrut lime leaves, torn (or zest of 1 lime)

2–3 Thai chilies (or 1 jalapeño)

Big pinch salt

1 tbsp water

Order matters:

Ginger/galangal + salt → lemongrass → chilies → lime leaves → water

No mortar? Totally fine:

🔪 Knife + board: mince, then smear with knife

⚡ Food processor: pulse with water

🥖 Zip-top bag + bottle: smash and roll

🌱 Stir-Fry Ingredients

Choose your protein:

8–12 oz chicken thighs or breasts, bite-size

OR14 oz extra-firm tofu, well-drained, cut into 1-inch pieces

½ tsp salt (for chicken or tofu)

3 tbsp neutral oil (divided)

3–4 cups mixed veg

(green beans, carrots, snap peas, bell pepper, bok choy, broccoli)

2 tbsp soy sauce or tamari

1 tsp sugar

To finish:

🌿 Thai basil or cilantro

🍋 Lime wedges

🥜 Optional peanuts

🔥 Cooking Method

1️⃣ Prep Protein (2 min)

Chicken: Toss with ½ tsp salt. Done.

Tofu: Pat dry really well. Toss with ½ tsp salt.

(Optional but excellent: 1 tsp oil + 1 tsp cornstarch for extra crisp edges.)

2️⃣ Cook Protein (3–4 min)

Heat wok or large skillet very hot.

Add 1 tbsp oil.

Add protein in a single layer.

Don’t touch for 30–45 seconds.

It will release when it’s ready.

Stir-fry until lightly browned and just cooked.

➡️ Remove to plate.

3️⃣ Veg + Aromatics (4–5 min)

Add 1 tbsp oil.

Hard veg first, anything that needs the high heat and some time to soften (ie carrots, green beans)

Lower heat to medium.

Add remaining 1 tbsp oil, then aromatic paste.

Stir constantly 30–60 seconds until deeply fragrant.

If it sticks, splash in 1 tbsp water.

You’re blooming, not burning 🌸🔥

Add Softer veg next, anything that would be best just lightly sauteed and mostly crispy.

By blooming the aromatics in between, you deepen the flavors and get them really permeated into the vegetables, not just on top.

4️⃣ Bring It Together (2–3 min)

Return protein to pan.

Add soy sauce + sugar.

Toss until glossy, sizzling, and evenly coated.

5️⃣ Finish (Off Heat)

Turn off heat.

Tear in herbs.

Squeeze lime. Taste. Adjust.

Top with peanuts if using.

🍚 Serve over rice or noodles.

✨ Done.

And hey—if paid membership isn’t doable, we get it. But even a one-time donation keeps the feast going. Thanks for being part of this table.

Bites of the week:

Freezer Fave: For the nights when you need a good, 10 minute dinner, we’ve been loving these steam buns.

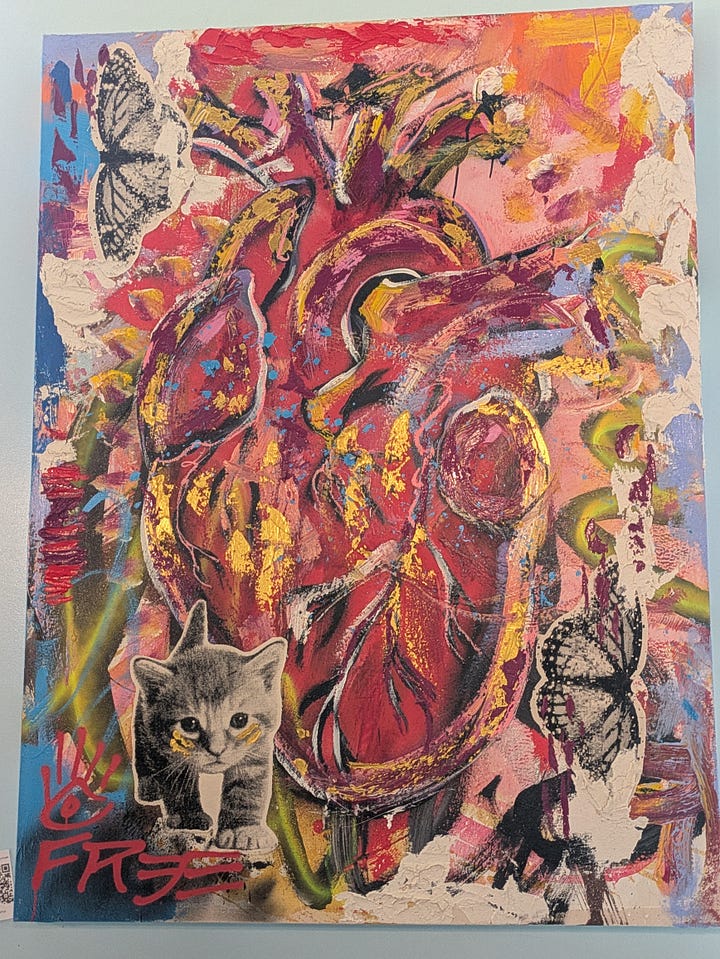

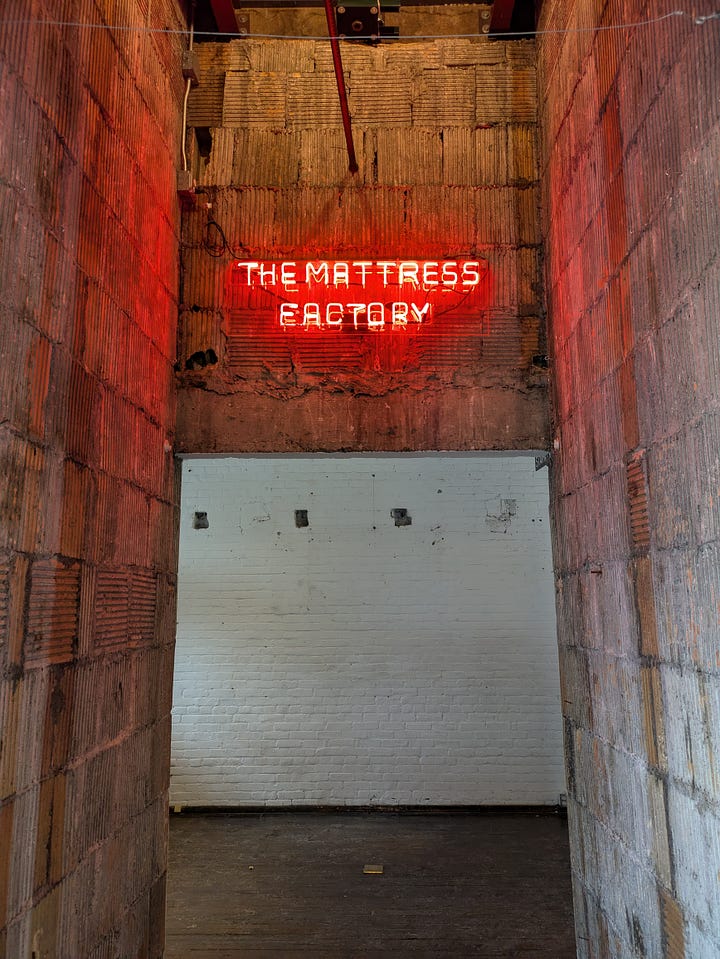

Short-rib Benedict with Sweet Potatoes from Square Cafe in Pittsburgh. We visited Steel City over MLK weekend and ate so much good food, which we hope to post about soon, but for now, this one is living rent-free in my head, and maybe now yours too.

🎧 What I’m Reading, Listening & Thinking About

A few things simmering on the back burner while the aromatics hit the oil.

Between Two Kingdoms by Suleika Jaouad This memoir sits with cancer not as a heroic arc but as a long recalibration, how prolonged suffering can narrow your world, sharpen your edges, and make it hard to remember anyone else is still out there living. It’s a book about learning how to reenter life, how care and patience are rebuilt slowly, and how nourishment is as emotional as it is physical. Heavy, yes. Also patiently generous.

Is American Food Actually Poison? Debunking MAHA movement and nutrition myths - What Now? with Trevor Noah. This episode cuts through the viral nutrition noise without swinging to the opposite extreme. Trevor Noah sits down with Dr. Jessica Knurick, a PhD in Nutrition Science specializing in chronic disease prevention, to unpack why food fear spreads so fast online. They talk protein panic, seed oil hysteria, raw milk, salt, and why absolutist food rules tend to create more stress than health. It’s a grounded, evidence-based conversation about eating well in a complicated food system, and a good reminder that context matters more than trends.

Up Next

Before we let curry get lush and layered in this Golden Middle Kitchen series, we slow down and look at the fat and structure that makes it work. We get into coconut and rice. Not just as a flavor, but as a structure. Why coconut fat is easier to digest than most people expect. How coconut cream and coconut milk behave differently in the pan. Why this is the difference between rich and overwhelming.

We’ll make something gentle and grounding. Something creamy. A bridge dish that teaches our hands what coconut does before we ask it to carry a full curry.

Same table.

New bowl.

See you there.

i love thai food so learning more about the aromatics involved just deepens my appreciation! i’m curious how you learned all this!